LIFE-SIZED STATUES FROM CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY

Showing 1–24 of 56 results

-

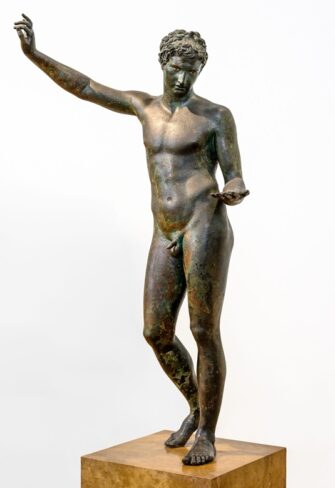

Hellenistic Prince

£26,330.00 -

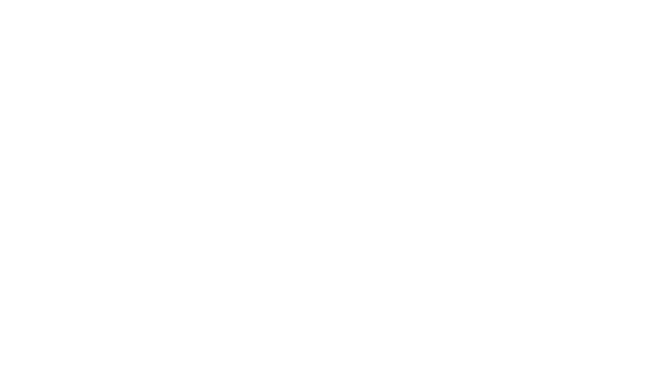

Jockey of Artemision

£37,400.00 -

Charioteer of Delphi

£17,760.00 -

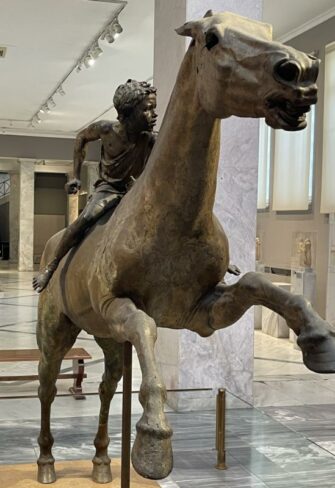

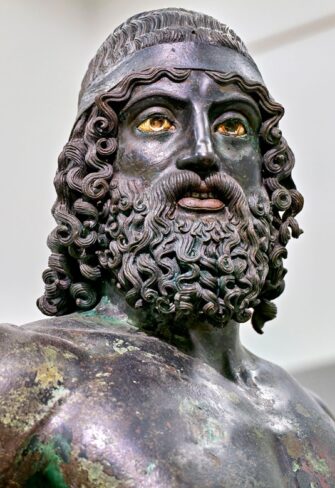

Riace A

£52,900.00 -

Riace B

£52,900.00 -

Boxer at Rest

£25,280.00 -

Artemision Bronze

£22,240.00 -

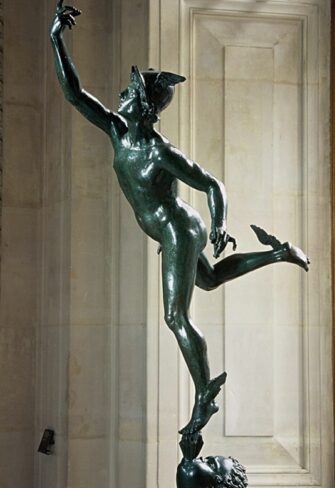

Mercury by Giambologna

£9,570.00 -

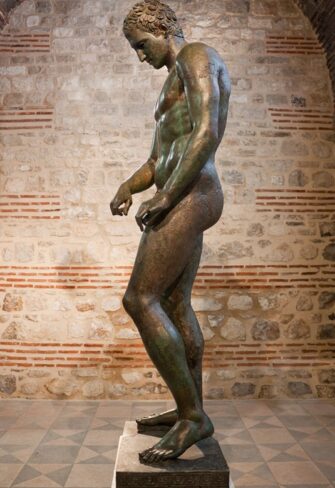

Croatian Apoxyomenos

£25,280.00 -

Marathon Boy

£24,000.00 -

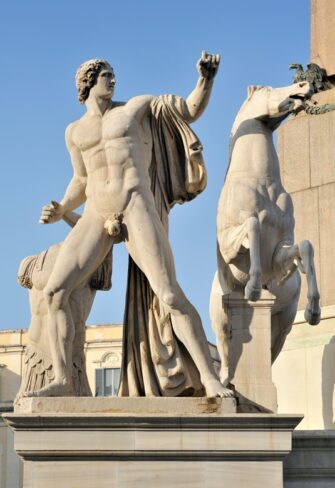

Dioscuri Statue Quirinal

£119,000.00 -

Augustus of Prima Porta

£24,000.00 -

Farnese Bull

£142,800.00 -

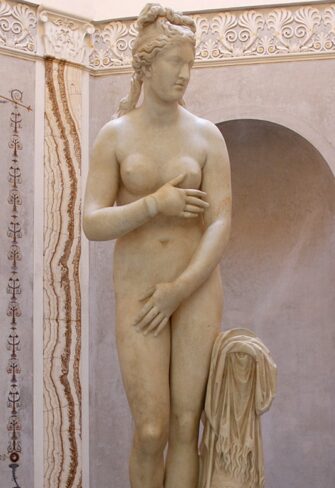

Capitoline Venus

£25,280.00 -

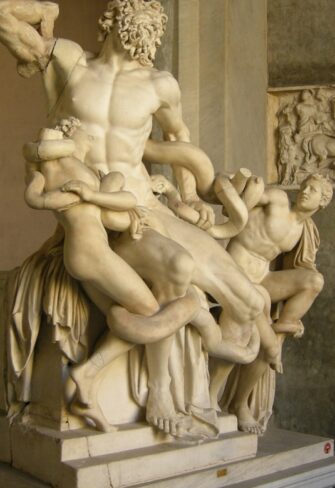

Laocoon and His Sons

£54,400.00 -

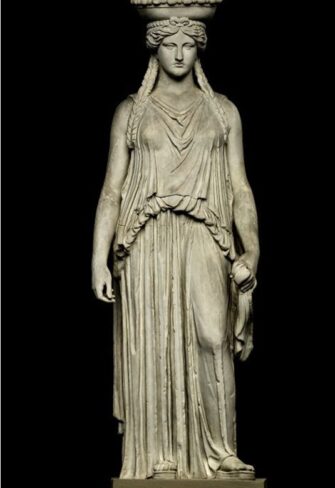

Erechtheion Caryatid

£26,800.00 -

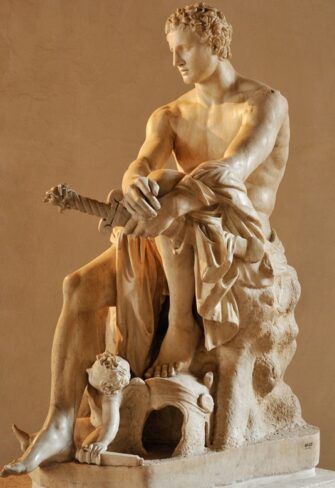

Ludovisi Ares

£30,560.00 -

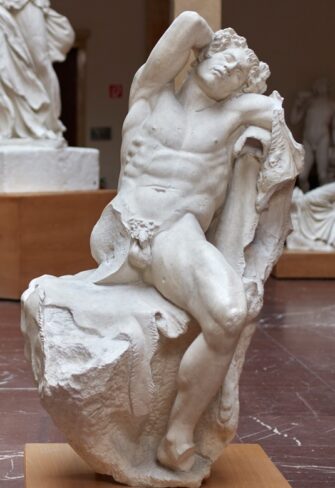

Barberini Faun

£32,960.00 -

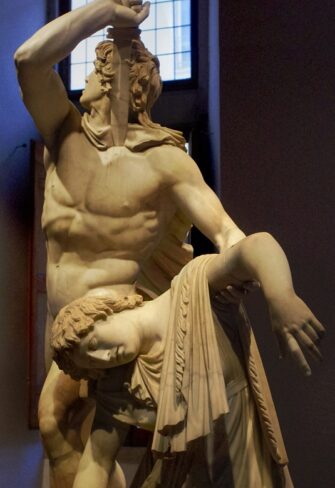

Ludovisi Gaul

£34,400.00 -

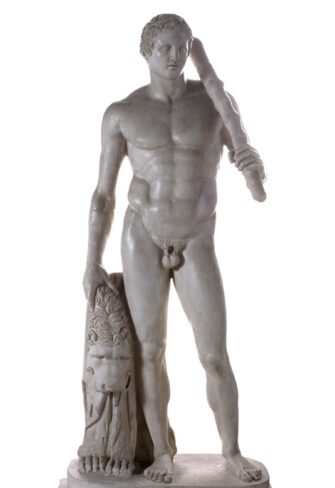

Lansdowne Heracles

£22,880.00 -

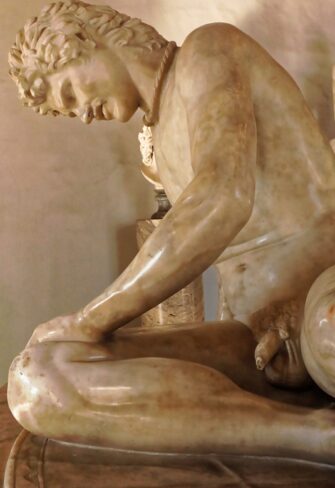

Dying Gaul

£21,440.00 -

Amazon Mattei

£22,880.00 -

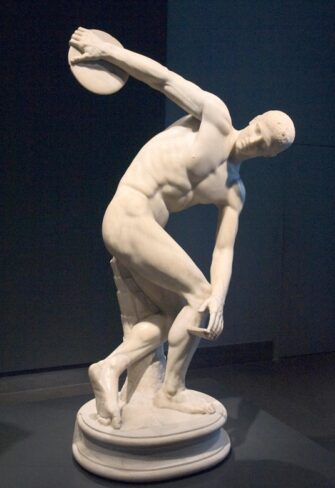

Discobolus Lancellotti

£19,600.00 -

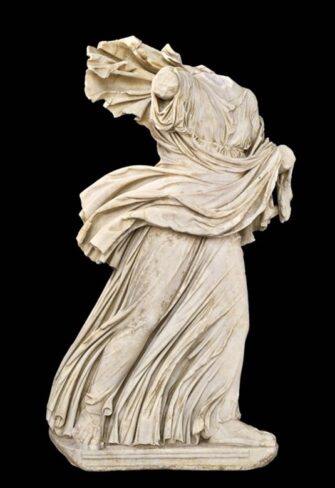

Chiaramonti Niobid

£30,800.00

Ancient Garden Sculptures for Garden Architecture – Life-Size, in Bronze or Marble, Museum-Quality Replicas

Our life-size replicas of ancient sculptures in bronze or marble are fundamental to classical Garden Architecture and refined Garden Design. Inspired by the masterpieces of ancient Greece and Rome, they bring cultural depth, architectural harmony, and timeless elegance to gardens, parks, and outdoor estates.

Over 50 Authentic Replicas of the World’s Most Celebrated Classical Statues

We offer an exclusive collection of over 50 museum-quality replicas of the most famous classical sculptures, faithfully reproduced at life-size scale. Each bronze piece is cast using moulds taken directly from museum originals, ensuring extraordinary authenticity and detail.

These sculptures are more than decoration: they are essential elements of Garden Architecture, used by leading landscape architects, garden designers, and art collectors worldwide. Crafted to museum standards, our bronze statues and marble busts are also chosen by film studios seeking historical accuracy, while their originals are exhibited in renowned museums across the globe.

From Craft to Placement – The Art, History, and Precision of Our Replicas

Locations for the Placement of Ancient Statues

In exceptionally designed gardens and parks, alongside high horticultural artistry and exceptionally beautiful design, the use of top-notch furnishings often shines. Whether it’s furniture or garden statues and sculptures. Now original antique statues are not or very rarely available for sale. Since their rediscovery in the Renaissance, costly replicas have such been made for castles, their parks, and concurrently for the mansions of the bourgeoisie who have attained great wealth. During this time, a canon for the placement and positioning of these artworks formed and developed into modern times. In our online shop, you’ll find an overview of particularly beautiful locations for ancient statues. Additionally, we provide you with an overview of some publicly accessible gardens and parks, each boasting an impressive collection of ancient sculptures, along with specific details on where each statue can be seen.

Historical Significance of the Offered Replica Sculptures

The statues of ancient Greece, primarily bronze statues, continue to be culturally significant for our Western civilization.

After Rome rose to world power, a large number of these Greek artworks made their way to Rome, some plundered, some acquired, and were copied and reinterpreted in Rome. A multitude of precise copies of the most beautiful works of ancient Greece were created for the Roman art market. In almost all cases, the lost Greek bronze originals are only known to us through their Roman marble copies.

However, most works of the ancient world have likely been lost forever during the turmoil and dark centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire. Many of the most beautiful statues were destroyed or vandalized even before then by fanatical Christians. Bronze statues were melted down in times of war, marble statues were left to their fate after the decline of ancient sites, used as building materials, or burnt into lime in early medieval lime kilns.

Of the over fifty replicas of ancient statues offered in our online shop, only nine statues are based on surviving original ancient Greek bronze statues. All other replicas offered are based on Roman marble statues that were created based on a Greek original bronze.

Plaster Casts for Casting Garden Statues and Busts

The basis for a perfect replica of the original is a plaster cast of the original. These plaster casts often date back two centuries. Many of them were taken from the originals found in Rome, mostly from the mid-18th century to the early 19th century. They were then exhibited for study purposes, mostly at a university, in so-called plaster cast collections. They often also came into private ownership, especially when the purchase of the original was too expensive or the original was not for sale.

Famous sculptors of the mentioned era, such as Bertel Thorvaldsen, Antonio Canova, Andreas Schlüter, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, and others, had their own plaster cast collections of the antiquities found at that time. These served as teaching aids for their students and as templates for their own works. These plaster casts were often supplemented and completed if the ancient original was not completely preserved.

Bronze Casting in the Lost Wax Process

The lost wax process is a method used to cast complex metal shapes. It is thousands of years old and is also used for the bronze casting replicas offered here.

The plaster cast serves as the basis for the required casting mold. Based on the data from the plaster cast, we create a plastic model. The plastic model is meticulously compared with the plaster cast and photos of the original and, if necessary, adjusted. When everything is perfect, the negative casting mold is taken from this plastic model. Then, liquid bronze is poured into this negative mold to create a positive bronze sculpture. Each of these steps is meticulously monitored to ensure that the cast replica matches the plaster cast and the original in the museum 1:1.

For bronze casting, we use bronze composed of at least 90% to 95% copper (CU) and 5% to 10% tin (SN). The exact composition varies within this range depending on the size and complexity of the statue. The amount of tin added influences the castability, corrosion resistance, and tensile strength of bronze castings. This alloy closely matches most of the ancient bronze alloys passed down through the ages and has proven itself over millennia. Bronze artifacts found in Pompeii and analyzed by the Goethe University Frankfurt in 1998 almost consistently had a composition of 90% CU with 10% SN. They also had lead additives in many cases, ranging from 0.01 to 0.02%.

Marble Casting and Sculpture Carving by the Sculptor

In addition to traditional bronze casting, we offer two other methods for replicating the garden tatues and busts shown here: marble casting from powdered genuine marble and sculptors carving the garden statue from a single marble block. If this form of work is suitable for your replica statue, please feel free to contact us. We welcome your email or call.

Buying Marble Casting Garden Sculptures made from Powdered Genuine Marble

Most ancient sculptures are visually known to us through Roman sculptures carved in marble. Mostly created based on a then-still-existing Greek original from bronze casting. And now exhibited in the most beautiful museums that Europe has to offer. So there is indeed a desire to buy one’s own replica in marble rather than bronze. An easy and absolutely precise method for creating museum-quality replicas is called “cast marble.”

In this process, a marble block is ground into very small grains. The resulting marble sand is then liquefied, mixed with adhesives, poured into molds, and hardened there. The process has been known since the mid-19th century and has been continually refined. To ensure that the resulting cast marble statue looks like real marble (from which it is made), the choice of the right marble, the right grain size, and the perfect recipe for the added adhesives are essential.

For the production of the replica garden statue, we use the finest white marble. We have plaster casts of the original to make the molds. We achieve stability, weather resistance, and a brilliant surface of artificial marble with the best mixture of ground marble and chemical adhesive additives. We are happy to provide you with a sample.

Parallel Materials available on the Market

In garden centers, there are often casts made of concrete (cast concrete) or similar materials available. Mostly, these are statues of ‘David’ and ‘Venus’. The casting templates for these are usually of such poor quality that they give a tacky impression of the statues. Additionally, the sizes are not original. Thus, the initial impression of these concrete statues doesn’t bode well.

Recarving the Garden Sculpture by Marble Block Sculptors

As a special service, we offer to have the replica recarved by a sculptor from a marble block of your choice. Depending on the complexity of the requested garden statue, this is a demanding task. Ultimately, it can only be mastered by sculptors who practice this daily in regions and environments where this highly specialized form of sculpting has been cultivated for generations. Such sculptors are found today in very few places, including Italy and China. In Italy, Carrara has been the center since ancient times, while in China, there are two provinces south of Beijing. Similar to Carrara, they have their own marble of what’s known as imperial quality for the Beijing court and a sculpting tradition that has been nurtured over countless generations.

It’s not uncommon for ancient statues discovered since the Renaissance to be reworked by famous sculptors of European royal courts. Just as the ancient Romans reworked statues of the ancient Greeks, creating copies that were often considered more attractive than the original, which were then copied or plaster casts made of them. As an example, the so-called Uffizi Wrestlers can be mentioned. On behalf of Le Nôtre, the French sculptor Philippe Magnier freestyled a replica of the group from a marble block for Versailles around 1685. This marble copy was so popular that plaster casts were made of it, rather than of the original in the Uffizi. It now stands in Paris.

Creating a replica from a marble block faithful to the historical model requires tradition, skill, and an understanding of the formal repertoire, canon of forms, of these special statues. The sculptors commissioned by us possess these qualifications. Usually, a new plaster cast is first created as a working template for the sculptor. Often, a cast of the most difficult part suffices, often that’s the head. Some sculptors additionally create their own model from clay, mostly of the head, to maintain this special connection to the statue and the sculpting process.

What we offer here is, therefore, a replica, but an artistically freely created, individual replica garden statue made of genuine marble.

Identifying Faulty Replicas

Replicas of garden statues and busts that are cast without a precise plaster cast or accurate scans only reproduce the outline of the statue, more or less. Often, this isn’t the case, especially if proportions or sizes have been altered for cost reasons. But even the outline lacks the sharpness of the original. What’s even worse is that the entire garden statue completely lacks fine structure. Musculature, hair, eyes, mouth are without depth, without sharpness. It’s all smoothed and rounded like with sandpaper, and appears flat, devoid of expression.

Why Aren’t All Replica Statues Priced in the Online Shop?

A whole series of bronze statues offered by us in our online shop are priced as “Price on request” or without a price. The reasons for this are diverse.

Choice of Art Foundry for the Replica Statue

Especially large garden statues can only be cast in highly specialized art foundries. These art foundries operate worldwide. They are often booked with major special orders for two to three years and therefore not immediately available for delivery.

Lack of Plaster Casts for the High-Quality Reproduction

For some garden statues and busts, especially those found in recent times, there is still no plaster cast and one would have to be made first. Nowadays, this is rarely done to avoid disturbing the often-present color remnants of the former ancient painting on many statues.

Working with 3D Scans for Reproduction

Here, a 3D scan could achieve quite perfect results. In practice, however, this usually doesn’t work. Because the permission to scan is usually only obtained with great effort and the best connections, if at all. So, the only option is to compile an extensive photo collection of these usually world-famous statues, from which a scan is then created. The scan is then improved by archaeological restoration specialists based on the photo templates, so that ultimately a usable scan is obtained that largely corresponds to the original. This scan is then printed in life-size and revised by a highly experienced sculptor specializing in the restoration of ancient sculptures. The head of the statue is often the most difficult part, especially if it has rich, deeply curled hair that the scanning camera doesn’t capture accurately enough in its depth.

Comparison of the Replica on Site with the Original

We usually successfully resolve this issue of “heads with rich locks of hair” by taking the scanned, printed head to the museum and requesting permission to compare it with the original. However, this is not always allowed. In some museums, our sculptor was however allowed to carry out fine work on the head on-site or at least mark affected areas.

Subsequent Chiselling in the Casting Sculpture

A number of statues we offer feature fine chiselling, for example, for a stubble or a headband or decorative patterns on the original preserved base. These chisellings are not clearly visible in the plaster cast or the cast did not catch them at all. Here, we work with highly experienced chisel masters who create the chisellings based on image references with their fine instruments.

Conclusion

Hence, there are manifold and often entirely different reasons why we price some garden statues in our online shop as “Price on request.”

Echoes of Antiquity – Garden Statues, Voices Cast in Stone and Bronze

Life-size, museum-quality replicas of classical garden statues reviving a vision of garden architecture where art, intellect, and landscape are seamlessly entwined.

From Sacred Groves to Sculpted Estates

For millennia, garden sculptures have transformed gardens into far more than cultivated ground. They have served as a language—an expression of culture, intellect, and enduring taste. From the sacred sanctuaries of Greece to the villas of Rome, the terraces of the Renaissance, and the landscaped parks of Georgian England, statues have stood as eloquent witnesses to civilisation’s highest ideals.

Greece – Origins in the Sacred and the Philosophical

In ancient Greece, sculpture animated sanctuaries, gymnasia, and academies—spaces where devotion, education, and contemplation intertwined. Figures stood beneath the pines of Delphi, among philosophers in the Lyceum, and along the athletic grounds of Olympia, embodying a union of body, mind, and spirit. Though few originals survive, these early installations established an outdoor tradition later reimagined in the gardens of Rome.

Rome – Villas as Theatres of Art and Nature

The Romans perfected the integration of sculpture into private estates. The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum—its bronzes mirrored in still pools and framed by colonnades—and Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli exemplify a cultivated ideal where art, architecture, and landscape were inseparable. Pliny the Younger himself described statues set among cypresses and fountains in his Laurentian villa: cultivated leisure rendered in stone and bronze.

The Renaissance – Antiquity Reimagined

The Renaissance rekindled this classical dialogue with renewed purpose. Terraced gardens in Florence and the fountains of Tivoli placed Apollo, Hermes, and Venus within designed vistas—not simply as embellishment but as symbols of learning and taste. Restored fragments and new works in the classical style transformed gardens into curated worlds where art and intellect flourished side by side.

Baroque Grandeur and English Arcadia

Baroque France turned sculpture into theatre: Versailles displayed hundreds of mythological figures aligned along its sweeping axes and water features, dramatising cosmic order and princely power. A century later, the English landscape garden softened this grandeur, placing statues—Hermes by a shaded glade, Diana near an ornamental temple—within pastoral settings designed for reflection and repose.

Historicism and the Belle Époque – A Cultivated Revival

The 19th century revived classical sculpture as a mark of cultivated education and cosmopolitan refinement. Parks in Munich and Berlin framed ancient figures within tree-lined vistas, while British collectors commissioned fine bronze and marble casts from Naples and London, weaving echoes of the Grand Tour and museum culture into their own estates.

A Timeless Language for Modern Gardens

This tradition endures. The RIACE Collection offers over 50 life-size museum-quality replicas, each faithfully cast in bronze or carved in marble from moulds of original masterpieces. These works are not mere ornaments but architectural instruments—anchoring space, lending gravitas, and reconnecting gardens with the historic language of Garden Architecture.

To place such a sculpture in a garden is to join a lineage stretching across centuries: a quiet conversation in which voices cast in stone and bronze continue to speak, uniting art, intellect, and landscape in spaces of lasting beauty.

Garden Statues – From Sacred Groves to Grand Estates

For those who wish to explore further, the story of garden statues is as rich as it is enduring. From sacred groves and imperial villas to Renaissance terraces and the landscaped parks of the English countryside, these works have shaped the language of Garden Architecture for millennia. What follows traces their journey across cultures and centuries—garden statues not as mere ornaments, but as constant companions to civilisation’s gardens. Across ages and continents, from sunlit colonnades to shaded woodland glades, in the most celebrated sanctuaries of antiquity and the most renowned parks of Europe, these figures have stood in silent dialogue with their surroundings. Here, their stories unfold in detail.

1. Ancient Greece – Sculptures in Sacred Groves and Philosophical Gardens

The use of freestanding statues in ancient Greece is attested primarily in sacred and public contexts, rather than in private ornamental gardens as we know them today.

Documented contexts include:

• Sacred Groves (ἄλση): Statues of gods and heroes were placed in open-air sanctuaries, such as the Sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron or the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi.

• Gymnasia and Palaestrae: Centres of education and physical training that blended intellectual and athletic pursuits, often decorated with statues of deities and philosophers. The Lyceum in Athens, active from the 4th century BC, is a prime example with its garden-like setting.

• Athletic Grounds: Olympia and other venues displayed statues of victorious athletes, gods, and demi-gods, vividly described by Pausanias and supported by surviving inscribed bases.

• Plato’s Academy: Literary sources such as Diogenes Laertius confirm commemorative stelae and statues of philosophers within its grounds.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

Greek outdoor spaces were steeped in ritual, education, and athleticism, with sculpture amplifying their symbolic and sacred purpose. This differs fundamentally from today’s secular Garden Architecture. Rare survivors, such as the bronze Charioteer of Delphi, exemplify sacred display rather than garden ornament—later transformed by Roman villa culture.

2. Roman Antiquity – Villa Gardens as Stages for Sculpture

Rome introduced a documented garden culture in which sculpture served as both aesthetic and architectural device, blending Greek artistry with Roman ideals of private luxury. Indeed, for the first time in human history, we can truly speak of garden statues.

Examples include:

• Villa dei Papiri (Herculaneum): Excavated in 1750, this 1st-century BC villa housed over 80 sculptures—primarily bronze copies of Greek originals—arranged along pools, colonnades, and sightlines. Its plan inspired the Getty Villa in California.

• Hadrian’s Villa (Tivoli): The Canopus combined reflective pools with statues of Athena, satyrs, and caryatids, exemplifying the fusion of art, architecture, and landscape.

• Pliny the Younger (Epistulae II,17): Pliny described statues among cypresses and fountains in his villa garden, a vivid literary testament to Roman figural display.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

Garden Statues such as the Ludovisi Gaul, once displayed in Rome’s Gardens of Sallust, epitomise how Roman Garden Architecture fused art, water, and space to create cultivated, prestigious environments.

3. The Renaissance – Reviving Antiquity in Garden Design

In the 15th century, Renaissance patrons revived antiquity through study, collection, and reinterpretation. Gardens became theatres of humanism, where garden statues signalled intellect and taste.

Key examples:

• Villa Medici, Fiesole (c. 1450): Terraced gardens integrating antique busts and garden statues, as noted in letters by Marsilio Ficino.

• Villa d’Este, Tivoli (from 1550): Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este combined garden statues, such as Hercules, Venus, and Neptune with fountains and grottoes in a rich classical programme.

• Giambologna’s Hermes (Venus Fiorenza, Boboli Gardens): Renaissance sculptors restored and reimagined fragmented antiquities, aligning them with contemporary ideals.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

This era introduced the “erudite garden”: cultivated landscapes enriched by classical references, where restored antiquities and and finely crafted garden statues projected learning and sophistication—a concept highly sought after once again.

4. The Baroque – Sculpture as Dramatic Theatre in Garden Architecture

In the Baroque, gardens became grand stages where garden statues and symbolism embodied princely authority and cosmic order.

Illustrative cases:

• Versailles: Designed by André Le Nôtre, its 300-plus garden statues—Apollo, Latona, Enceladus—reinforced Louis XIV’s solar imagery.

• Bosquet de l’Encelade: A monumental bronze of Enceladus amid waterworks dramatized myth and hydraulics in unison.

• Schönbrunn Palace (Vienna): The Neptunbrunnen (1773) demonstrates axial geometry accentuated with classical garden statuary.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

Baroque gardens crystallised the structural and symbolic roles of garden statues—principles that remain influential in historically informed Garden Architecture today.

5. The English Landscape Garden – Sculpture in Arcadian Nature

By the 18th century, English gardens abandoned rigid geometry for pastoral “naturalism,” drawing inspiration from the Arcadian landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. Garden statues lent these vistas points of meaning and cultivated association.

Examples:

• Stowe Landscape Gardens: A Hercules garden statue and the Temple of Ancient Virtue created intellectual “stations” within curated scenery.

• Rousham Park: William Kent placed garden statues of Venus, Pan, and Diana along meandering paths, fusing classical allusion with sentiment.

• Painshill Park: Apollo and the Muses punctuated vistas framed by follies and woodland glades.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

Here, garden statues bridged nature and culture—an approach perfectly suited to integrating our museum-quality garden statue replicas into today’s refined Garden Design.

6. Historicism and the Belle Époque – The Garden Statue as Cultural Capital

In the 19th century, the garden statue became a symbol of education, refinement, and cosmopolitan taste, gracing both civic parks and private estates.

Contexts include:

• Munich’s English Garden (1789): Garden statues framed pastoral scenes steeped in Greek allusion.

• Glienicke Park (Berlin): Prince Carl of Prussia aligned original garden statues and faithful replicas along terraces and axes.

• The Glyptothek, Munich (1830): Museum culture, supported by cast workshops such as Brucciani (London) and Chiurazzi (Naples), spurred the placement of accurate garden statue reproductions in cultivated landscapes.

Relevance to Garden Architecture:

The RIACE Collection continues this lineage, reviving garden statues as anchors of design, aesthetic expression, and intellectual gravitas in contemporary Garden Architecture.

Conclusion: Garden Statues as the Defining Voice of Timeless Garden Architecture

From Greece’s sacred groves and Roman villas to Renaissance terraces and English estates, freestanding garden statues have defined the language of Garden Architecture. Our life-size, museum-quality garden statue replicas, faithful to ancient originals, extend this tradition into the present. They serve not as decoration, but as focal points of cultural resonance—transforming gardens into cultivated spaces where art, intellect, and nature meet in quiet harmony.

View the Full Collection of Life-Size Garden Statues (above)